In September 2023, Earth rumbled.

Seismic tracking all over the place the globe registered a extraordinary sign that repeated each 90 seconds over a whopping 9 days, truly fizzling out in some way by no means ahead of observed.

Then the similar factor took place a month later. Subsequent research of the ones indicators made up our minds that the reason for that trembling was once most likely a large megatsunami rocking backward and forward, slapping in opposition to the edges of a fjord in Greenland – producing a status wave referred to as a seiche.

Now, scientists have after all in fact observed the development, in satellite tv for pc information captured whilst the development was once in development. It’s the remark had to ascertain that the reason for the seismic sign was once certainly a seiche, giving us a solution to the age-old query: if a seiche paperwork in a Greenland fjord and nobody is round to peer it, does it shake the planet?

“This study is an example of how the next generation of satellite data can resolve phenomena that has remained a mystery in the past,” says ocean engineer Thomas Adcock of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom.

“We will be able to get new insights into ocean extremes such as tsunamis, storm surges, and freak waves. However, to get the most out of these data we will need to innovate and use both machine learning and our knowledge of ocean physics to interpret our new results.”

According to the analysis of the seismic data, the trigger that unleashed the megatsunami was a melting glacier that sent two giant landslides toppling into the remote Dickson fjord in East Greenland. The resulting splashes generated powerful tsunamis that, with nowhere else to go, sloshed back and forth for days, reaching a peak height of 7.4 to 8.8 meters (24.3 to 28.9 feet).

Because of the remote location, however, no one actually saw either event – not even a military vessel that visited the fjord three days into the first one.

But humanity has eyes in the sky. There’s a satellite mapping technique called altimetry that measures the height of the surface of the planet (including bodies of water) based on how long it takes a radar signal to travel down to the surface and bounce back up again.

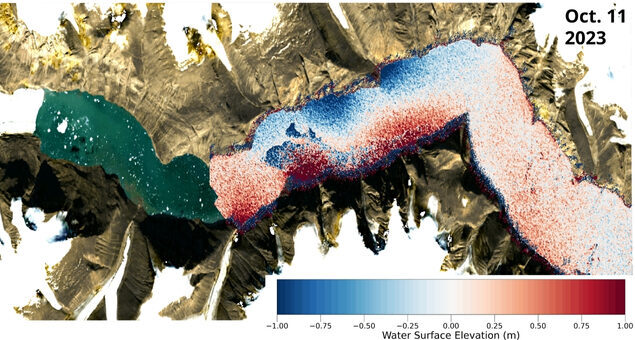

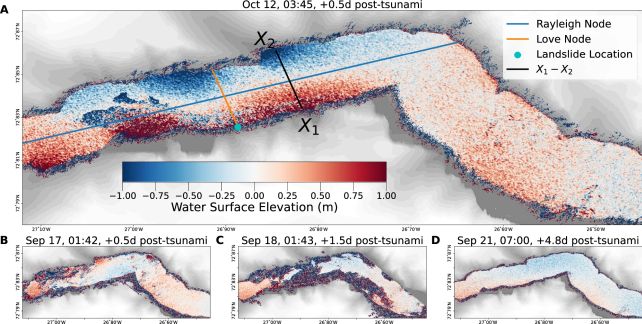

Most altimetry measurements were unable to record the seiches, because the resolution isn’t high enough and the measurements are taken too far apart in time. But a NASA mission launched in 2022 called the Surface Water Ocean Topography (SWOT) satellite has an instrument that is able to take measurements of the height of water with unprecedented precision.

The satellite just so happened to have taken measurements at intervals during the days following both events. So the researchers on the new study used this data, collected by SWOT’s Ka-band Radar Interferometer, to compile elevation maps of the fjord.

Their results showed clear and significant height variations in the water, which was rising as a 2-meter standing wave reverberating back and forth across the fjord.

That was it: the team had finally laid eyes on the seiches that were thought to have sent such strange signals rumbling around the world.

The next step was to link the two phenomena. By comparing their observations to seismic data, the researchers were able to reconstruct the characteristics of each wave, and the evolution of each event, even for time periods that the satellite had not observed. They were able to rule out other possible explanations for the seismic signals, and confirm that the seiches were responsible.

It’s a beautifully tidy result that will help us study such events in the future.

“Climate exchange is giving upward push to new, unseen extremes. These extremes are converting the quickest in far off spaces, such because the Arctic, the place our talent to measure them the usage of bodily sensors is restricted,” says engineer Thomas Monahan of the University of Oxford.

“This find out about displays how we will leverage the following technology of satellite tv for pc Earth remark applied sciences to review those processes. SWOT is a recreation changer for learning oceanic processes in areas akin to fjords which earlier satellites struggled to peer into.”

The analysis has been printed in Nature Communications.

Global News Post Fastest Global News Portal

Global News Post Fastest Global News Portal