When Isaac Newton wrote down his now-famed regulations of movement in 1687, he may have solely was hoping we would be discussing them these types of centuries later.

Writing in Latin, Newton defined 3 common rules describing how the movement of gadgets is ruled in our Universe, that have since been translated, transcribed, mentioned and debated at duration.

But in line with a thinker of language and arithmetic, we would possibly had been decoding Newton’s exact wording of his first legislation of movement relatively unsuitable all alongside.

Watch the video beneath to look a abstract of Hoek’s point of view;

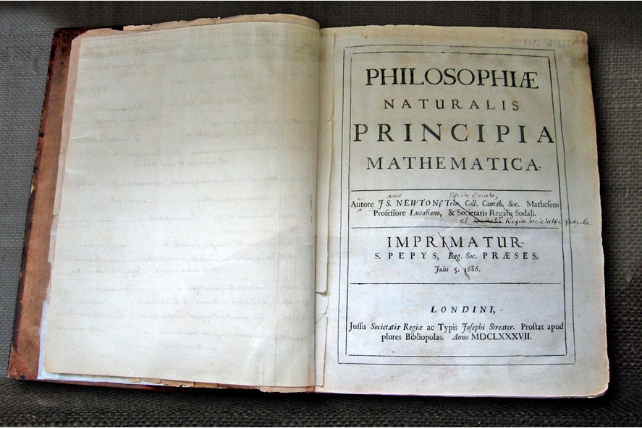

Virginia Tech philosopher Daniel Hoek wanted to “set the document instantly” after finding what he describes as a “clumsy mistranslation” in the original 1729 English translation of Newton’s Latin Principia.

Based on this translation, countless academics and teachers have since interpreted Newton’s first law of inertia to mean an object will continue moving in a straight line or remain at rest unless an outside force intervenes.

It’s a description that works well until you appreciate external forces are constantly at work, something Newton would have surely considered in his wording.

Revisiting the archives, Hoek realized this common paraphrasing featured a misinterpretation that flew under the radar until 1999, when two scholars picked up on the translation of one Latin word that had been overlooked: quatenus, which means “insofar”, not unless.

To Hoek, this makes all the difference. Rather than describing how an object maintains its momentum if no forces are impressed on it, Hoek says the new reading shows Newton meant that every change in a body’s momentum – every jolt, dip, swerve, and spurt – is due to external forces.

“By placing that one forgotten phrase [insofar] again in position, [those scholars] restored probably the most basic rules of physics to its unique splendor,” Hoek explained in a blog post describing his findings, published academically in a 2022 research paper.

However, that all-important correction never caught on. Even now it might struggle to gain traction against the weight of centuries of repetition.

“Some in finding my studying too wild and unconventional to take critically,” Hoek remarks. “Others suppose that it’s so clearly right kind that it’s slightly value arguing for.”

Ordinary folks might agree it sounds like semantics. And Hoek admits the reinterpretation hasn’t and won’t change physics. But carefully inspecting Newton’s own writings clarifies what the pioneering mathematician was thinking at the time.

“Quite a lot of ink has been spilt at the query what the legislation of inertia is in truth for,” explains Hoek, who was puzzled as a student by what Newton meant.

If we take the prevailing translation, of objects traveling in straight lines until a force compels them otherwise, then it raises the question: why would Newton write a law about bodies free of external forces when there is no such thing in our Universe; when gravity and friction are ever-present?

“The entire level of the primary legislation is to deduce the lifestyles of the pressure,” George Smith, a philosopher at Tufts University and an expert in Newton’s writings, told journalist Stephanie Pappas for Scientific American.

In fact, Newton gave three concrete examples to illustrate his first law of motion: the most insightful, according to Hoek, being a spinning top – that as we know, slows in a tightening spiral due to the friction of air.

“By giving this situation,” Hoek writes, “Newton explicitly displays us how the First Law, as he understands it, applies to accelerating our bodies that are topic to forces – this is, it applies to our bodies in the actual global.”

Hoek says this revised interpretation brings home one of Newton’s most fundamental ideas that was utterly revolutionary at the time. That is, the planets, stars, and other heavenly bodies are all governed by the same physical laws as objects on Earth.

“Every exchange in pace and each and every tilt in course,” Hoek mused – from swarms of atoms to swirling galaxies – “is ruled via Newton’s First Law.”

Making us all feel once again connected to the farthest reaches of space.

The paper has been published in the Philosophy of Science.

An previous model of this newsletter was once printed in September 2023.

Global News Post Fastest Global News Portal

Global News Post Fastest Global News Portal