A supermassive black gap within the early Universe has been noticed blasting out robust jets of plasma which are a minimum of two times so long as the Milky Way is extensive.

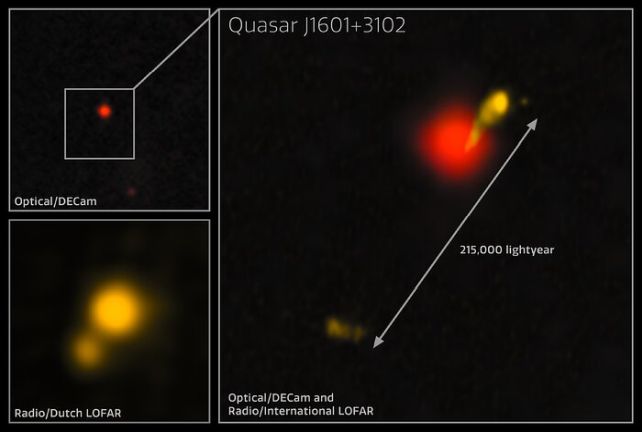

Its host galaxy is a quasar referred to as J1601+3102, and we are seeing it because it used to be not up to 1.2 billion years after the Big Bang. Spanning 215,000 light-years from finish to finish, that is the biggest construction of its sort observed in the ones early phases of the Universe’s formation, and astronomers suppose it could resolution some questions on how they develop.

“We were searching for quasars with strong radio jets in the early Universe, which helps us understand how and when the first jets are formed and how they impact the evolution of galaxies,” explains astrophysicist Anniek Gloudemans of the National Science Foundation’s NOIRLab.

Jets are a particularly interesting supermassive black hole behavior. When there is enough material close to a supermassive black hole in the center of a galaxy, it swirls around, forming a disk of material that feeds into the black hole, drawn in by its extreme gravity. That feeding often produces a quasar, blazing with light as the swirling material is heated by friction and gravity to temperatures of millions of degrees.

Not all the material falls onto the black hole beyond escape, though. Some of it gets diverted along the magnetic field lines outside the event horizon and accelerated to the black hole’s poles, where it is launched into space with tremendous speed.

These eruptions of material form jets, and they blast out into space for huge distances. The longest we’ve found to date are 23 million light-years from end to end, much later in the lifetime of the Universe.

However, they only emit light in radio waves, which makes them a little tricky to see. To identify J1601+3102, Gloudemans and her colleagues had to combine observations from multiple telescopes, including the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) Telescope in Europe, Gemini North in Hawaii, and the optical Hobby-Eberly Telescope in Texas.

These observations didn’t just reveal the extent of J1601+3102’s jets, they allowed the researchers to study the black hole. The amount of light emitted by the quasar activity can be analyzed to reveal the black hole’s mass.

It’s just 450 million times the mass of the Sun, a relatively modest size for a quasar black hole. And it’s not scarfing down matter at a particularly high rate, either. These properties suggest that quasars could be more varied than we generally assume.

“Interestingly, the quasar powering this huge radio jet does no longer have an excessive black gap mass in comparison to different quasars,” Gloudemans says. “This turns out to signify that you do not essentially want an exceptionally huge black gap or accretion price to generate such robust jets within the early Universe.”

The discovery used to be detailed in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Global News Post Fastest Global News Portal

Global News Post Fastest Global News Portal