A deep-sea expedition to one among Earth’s maximum far off island chains has surfaced shocking photos of the colourful ecosystems surrounding hydrothermal vents that scientists did not even know had been there.

The 35-day adventure aboard Schmidt Ocean Institute’s Falkor (too) analysis vessel used to be a part of the Ocean Census‘s race to file marine lifestyles prior to it’s misplaced to threats like local weather exchange and deep sea mining.

This expedition took a world crew of scientists to the South Sandwich Islands, within the South Atlantic close to Antarctica, which boasts the Southern Ocean’s private trench.

Despite going through subsea earthquakes, hurricane-force winds, towering waves, and icebergs, the team used to be rewarded with a trove of implausible new discoveries.

You may have already watched the expedition’s world-first pictures of a reside colossal squid, however a few of their different reveals deserve a second within the highlight.

Like this vermillion coral lawn thriving on Humpback Seamount, close to the area’s shallowest hydrothermal vents at round 700 meters deep (just about 2,300 toes).

The tallest vent chimney stood 4 meters (13 toes) tall, proudly wearing an array of lifestyles, together with barnacles and sea snails. Like drones in a New Year’s Eve sky, a fleet of shrimp whizzed spherical those submarine skyscrapers.

These hydrothermal vents, at the northeast facet of Quest Caldera, are the one South Sandwich Island vents explored by means of remotely operated automobile (ROV) to this point; we will’t wait to look what long run expeditions discover.

“Discovering these hydrothermal vents was a magical moment, as they have never been seen here before,” says hydrographer Jenny Gales from the University of Plymouth in the United Kingdom.

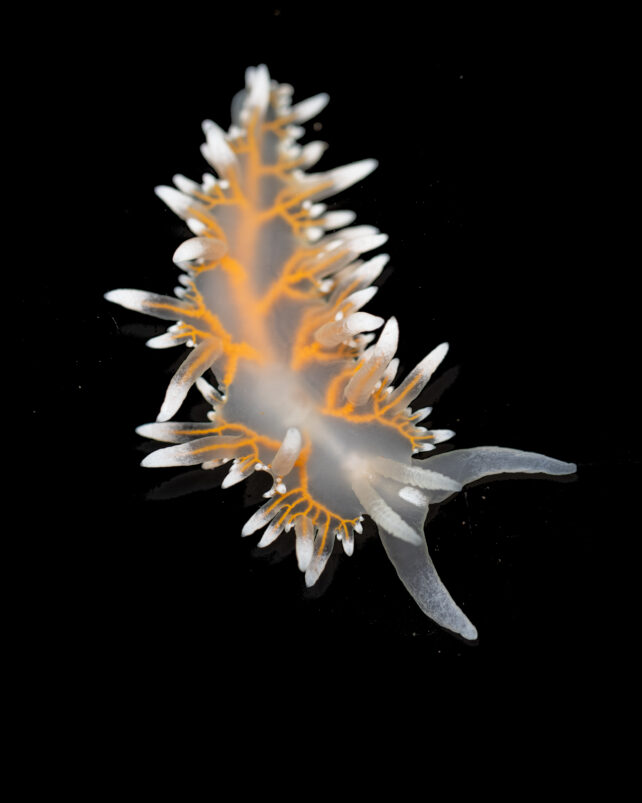

But positive specimens deserve a close-up: like this beautiful nudibranch, unspecified, which blackwater photographer Jialing Cai snapped at 268 meters deep within the near-freezing waters east of Montagu Island.

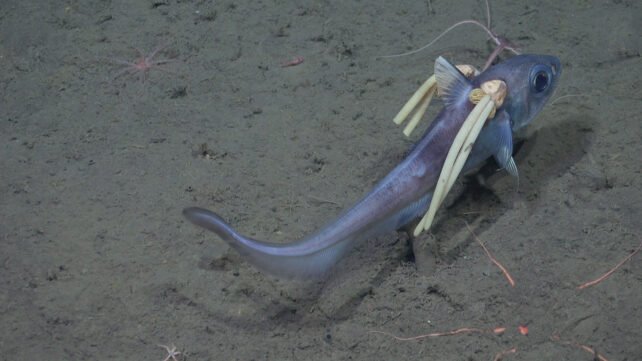

Nearby, a somewhat extra provoking second used to be captured: a grenadier fish with parasitic copepods – most probably Lophoura szidati – tucked into its gills like horrid pigtails.

And this stout little sea cucumber, recorded 650 metres under the ocean floor at Saunders East, with a gob filled with what we will be able to informally dub a deep-sea puffball.

Now, brace your self for the primary ever symbol of Akarotaxis aff. gouldae, a species of dragonfish that has refrained from our cameras for 2 years since its discovery.

Something else that no one’s observed prior to? Snailfish eggs on a black coral. Not even marine biologists knew this used to be a factor, till now.

“This expedition has given us a glimpse into one of the most remote and biologically rich parts of our ocean,” says marine biologist Michelle Taylor, the Ocean Census mission’s head of science.

“This is exactly why the Ocean Census exists – to accelerate our understanding of ocean life before it’s too late. The 35 days at sea were an exciting rollercoaster of scientific discovery, the implications of which will be felt for many years to come as discoveries filter into management action.”

Look behind-the-scenes aboard the Falkor (too) analysis vessel right here.

Global News Post Fastest Global News Portal

Global News Post Fastest Global News Portal