South American mummies have change into identified for his or her impressive tattoos, however an research has discovered the design inked into the cheek of an roughly 800-year-old lady buried within the area is exclusive in some ways.

While we people had been decorating ourselves with everlasting pores and skin artwork for hundreds of years, proof of the art work is incessantly misplaced to the sands of time. Tools had been discovered right here and there, however it is uncommon for the tattooed pores and skin itself to continue to exist.

In South America, despite the fact that, preserved tattoos are rather commonplace amongst millennium-old mummies, specifically since the coastal deserts the place they had been buried are perfect for protective comfortable tissue like pores and skin from decay.

A staff of anthropologists and archeologists led through Gianluigi Mangiapane from the University of Turin in Italy have taken a more in-depth have a look at the stays of 1 lady whose tattoos make her stand proud of the group.

The precise beginning of this actual mummy is sadly unknown, as a result of her stays had been donated to the Italian Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography just about a century in the past with necessarily no context instead of the Italian donor’s title and the reality she used to be filed below ‘South American artifacts’.

But there are some hints as to her origins. The manner her frame used to be seated in an upright, knees-bent place suggests a state of preservation referred to as a ‘fardo’, wherein the corpse is wrapped in lots of layers of material after which tied right into a package deal. This used to be a commonplace funerary apply in Paracas tradition within the Andean area, at the south coast of Peru.

Radiocarbon courting of the textile fragments that also hang to the lady’s frame published she lived between 1215 and 1382 CE.

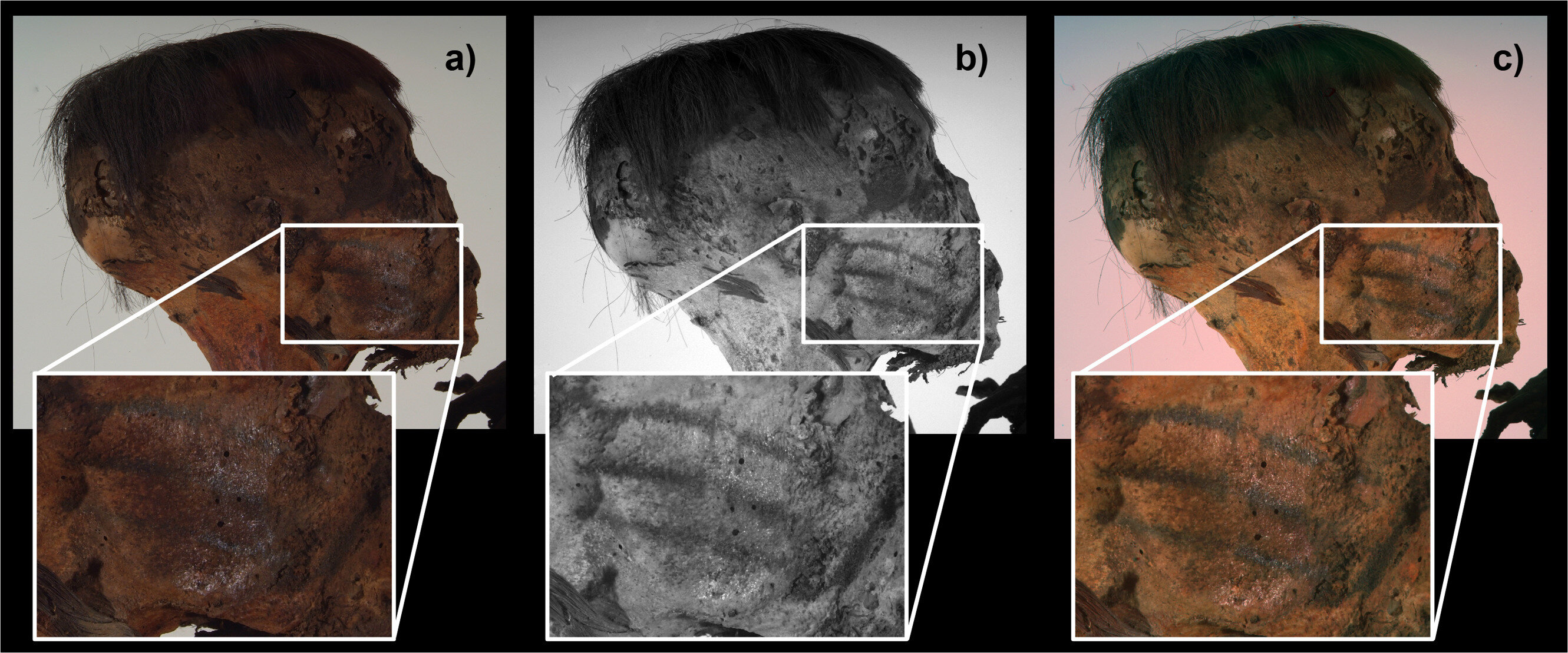

Her tattoos are slightly arduous to look due to the mummification procedure darkening her pores and skin, so the staff used an array of non-destructive imaging tactics to get a greater image of the unusually minimalist designs.

An S-shaped tattoo ornaments considered one of her wrists; a commonplace placement for tattoos amongst South American cultures the time. Yet even that design is far more practical than the ones usually noticed at the palms, wrists, forearms, and toes in their mummies.

What stands proud maximum, in fact, is the mother’s bizarre cheek tattoos, which can be additionally apparently easy of their design. Among historic South American tattoos, the authors write, “cheek tattoos are less present (or underestimated due to difficulties in finding preserved skin).”

“The three detected lines of tattooing are relatively unique: in general, skin marks on the face are rare among the groups of the ancient Andean region and even rarer on the cheeks,” they record.

Chemical research suggests the tattoo’s black ink used to be created from magnetite, a black, steel, and magnetic iron ore. That’s bizarre, too: archaeologists have a tendency to think black tattoo ink used to be created from charcoal, despite the fact that the authors indicate that few research if truth be told examine the ink composition at a chemical degree. This roughly pigment, the authors say, has now not been reported in another South American mummies.

“The intentional use of only charcoal pigments, which are the most commonly used materials according to the literature, can be ruled out in this case,” they write.

“The results highlight the presence of magnetite, a commonly used material both in present and past cultures, as well as of other iron-rich phases of the pyroxene silicates group… with a small amount of carbon-based materials, possibly not intentionally added (e.g. due to pigment preparation procedures).”

What do her distinctive tattoos imply, you ask? Well, clearly they had been supposed to be noticed through others, since they should not have been lined through clothes. But what they had been supposed to keep up a correspondence, precisely, stays a thriller.

The analysis used to be revealed in Journal of Cultural Heritage.

Global News Post Fastest Global News Portal

Global News Post Fastest Global News Portal