BBC News, Yorkshire

Science correspondent, BBC News

University of York

University of YorkBite marks discovered at the skeleton of a Roman gladiator are the primary archaeological proof of battle between a human and a lion, mavens say.

The stays have been came upon all the way through a 2004 dig at Driffield Terrace, in York, a website online now considered the arena’s simplest well-preserved Roman gladiator cemetery.

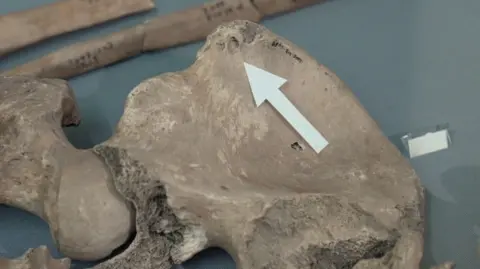

Forensic exam of the skeleton of 1 younger guy has printed that holes and chew marks on his pelvis have been possibly led to through a lion.

Prof Tim Thompson, the forensic skilled who led the find out about, stated this used to be the primary “physical evidence” of gladiators preventing giant cats.

“For years our understanding of Roman gladiatorial combat and animal spectacles has relied heavily on historical texts and artistic depictions,” he stated.

“This discovery provides the first direct, physical evidence that such events took place in this period, reshaping our perception of Roman entertainment culture in the region.”

Experts used new forensic ways to analyse the injuries, together with 3-d scans which confirmed the animal had grabbed the person through the pelvis.

Prof Thompson, from Maynooth University, in Ireland, stated: “We could tell that the bites happened at around the time of death.

“So this wasn’t an animal scavenging after the person died – it used to be related together with his demise.”

As well as scanning the wound, scientists compared its size and shape to sample bites from large cats at London Zoo.

“The chew marks on this explicit particular person fit the ones of a lion,” Prof Thompson told BBC News.

The location of the bites gave researchers with even more information about the circumstances of the gladiator’s death.

The pelvis, Prof Thompson explained, “isn’t the place lions most often assault, so we predict this gladiator used to be preventing in some type of spectacle and used to be incapacitated, and that the lion bit him and dragged him away through his hip.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe skeleton, a male aged between 26 and 35, had been buried in a grave with two others and overlaid with horse bones.

Previous analysis of the bones pointed to him being a Bestiarius – a gladiator that was sent into combat with beasts.

Malin Holst, a Senior Lecturer in Osteoarchaeology at the University of York, said in 30 years of analysing skeletons she had “by no means noticed anything else like those chew marks”.

Additionally, she said the man’s remains revealed the story of a “brief and quite brutal existence”.

His bones were shaped by large, powerful muscles and there was evidence of injuries to his shoulder and spine, which were associated with hard physical work and combat.

Ms Holst, who is also managing director of York Osteoarchaeology, added: “This is a massively thrilling in finding as a result of we will now begin to construct a greater symbol of what those gladiators have been like in existence.”

The findings, which have been published in the Journal of Science and Medical Research PLoS One, also confirmed the “presence of huge cats and doubtlessly different unique animals in arenas in towns reminiscent of York, and the way they too needed to shield themselves from the specter of demise”, she said.

Experts said the discovery added weight to the suggestion an amphitheatre, although not yet found, likely existed in Roman York and would have staged fighting gladiators as a form of entertainment.

The presence of distinguished Roman leaders in York would have meant they required a lavish lifestyle, experts said, so it was no surprise to see evidence of gladiatorial events, which served as a display of wealth.

David Jennings, CEO of York Archaeology, said: “We would possibly by no means know what introduced this guy to the sector the place we imagine he can have been preventing for the leisure of others, however it’s outstanding that the primary osteoarchaeological proof for this type of gladiatorial battle has been discovered to this point from the Colosseum of Rome, which might were the classical global’s Wembley Stadium of battle.”

Global News Post Fastest Global News Portal

Global News Post Fastest Global News Portal